Rocket Men and Systems Engineering

In which Apollo 8 is my favorite terrible idea that actually worked.

June 3, 2019

The crew of Apollo 8. From left: Frank Borman, Bill Anders, and James Lovell. Photo taken by NASA, owned by the Smithsonian Institution.

Note: this piece was originally written as a book report for Purdue's AAE 35103: Aerospace Systems. The assignment was to read a book that was somehow related to systems engineering, summarize the book, explain its connections to systems engineering, and provide feedback on it. I chose Robert Kurson's Rocket Men, about the Apollo 8 mission, after hearing an interview with Kurson on the podcast The Skeptics' Guide to the Universe.

"THANKS. YOU SAVED 1968."

These final words, directly quoting one of thousands of telegrams written to the astronauts of the Apollo 8 mission, contain within them the soul of Robert Kurson’s Rocket Men. If Kurson has a thesis statement, this is it. Apollo 8 (or, as the book’s subtitle describes it, “The Daring Odyssey of Apollo 8 and the Astronauts Who Made Man’s First Journey to the Moon”) was a crucial source of inspiration and national pride at the end of a year marked by prejudice, protests, and political discontent. Rocket Men is non-fiction, built from years of research and personal interviews with people involved in Apollo 8; but the book reads like an epic tale on the scale of The Odyssey. It is, at its core, a story. It is a story of courage, ingenuity, and, yes, American exceptionalism (we’ll get to that). But Rocket Men is also a story about systems engineering. It’s a story about functional analysis and concept generation and failure rates. It’s a story about a group of human beings cooperating to create one of the most intricate, complicated systems of components and sub-components and sub-sub-components ever built and trying very hard to make sure this system doesn’t blow up and ruin Christmas forever.

"Earthrise", taken by Bill Anders on Christmas Eve, 1968. Original photo from NASA, downloaded from The Atlantic.

Rocket Men begins in medias res by setting the scene of Apollo 8’s launch aboard the Saturn V rocket four days before Christmas in 1968. Kurson establishes the weight of the situation. The Saturn V has never flown with men aboard and has a 1-1 record of unmanned tests (one success, one catastrophic failure). The three astronauts aboard plan to shatter the world altitude record of 853 miles, becoming the first to visit the Moon. The United States from which the mission will launch is broken by riots, assassinations, and an extremely unpopular war. The entire mission has been scraped together in four months and many engineers and scientists question whether the crew will survive. The crew questions it too. In a charming moment, one of the astronauts notices a wasp building a nest on the outside of one of the rocket’s windows. The engines ignite.

From here, Kurson takes us back in time to August 3, four months earlier, on a beach in the Caribbean where an engineer named George Low has a downright stupid idea: what if NASA tried to send astronauts to the Moon in December? Kurson continues the story more or less chronologically. In California, astronaut Frank Borman prepares a test of the Apollo command module with the help of his crewmates, Jim Lovell and Bill Anders. Borman gets a call from NASA training manager Donald Kent “Deke” Slayton. A few hours later, Borman and Slayton are in a private meeting in Houston. Slayton explains that Apollo 8 may be headed to the Moon in December. Borman agrees to command the mission.

Leading up to this, Kurson explains, Low had held meetings with various experts and managers, including NASA’s legendary director of flight operations, Christopher Columbus Kraft. Along the way, everyone seemed to agree that the idea was impossible. But, one by one, everyone agreed to consider it – study the risks, rule out any truly insurmountable issues, and, through it all, not let anyone know they were planning this.

Borman returns to California and tells his crew about the new Apollo 8 plan. Lovell and Anders are in. The men tell their families. Meanwhile, NASA engineer Thomas Paine and Air Force general Samuel Phillips have the unenviable job of proposing the mission to NASA administrator James E. Webb. Webb screams into the telephone, listing every reason that this is a dangerous, insane idea. And yet, he doesn’t say no. A day later, Webb calls back: the new Apollo 8 plan is historically risky and could spell the end of NASA if it fails, but it could be a much-needed boost if it succeeds. Webb gives his verdict: if Apollo 7 completes all its mission objectives in the fall, Apollo 8 will be go. To the men working on Apollo 8, Apollo 7 might as well have already succeeded.

On August 18th, Borman meets with Kraft and a number of NASA’s top talent to draft an agenda for Apollo 8. At this point, the normal Washington bureaucracy has been thrown out the window. There’s no time for that. What comes next is four hours of arguing about mission priorities and what is and is not necessary for Apollo 8 to be considered a success. By 5 p.m., they have a plan: a six-day mission with ten lunar orbits, three television broadcasts, and a lot of very risky firsts. Oh, and one more thing: if all goes according to plan, the crew of Apollo 8 will be orbiting the Moon on Christmas. If all does not go according to plan, the crew may die on Christmas.

From here, the mission continues on an extremely rushed schedule, with nothing being ready as soon as people would like it to be. Throughout the book, Kurson delivers a consistent back-and-forth between the Apollo 8 story and the backstory before it – Borman’s friendship with Ed White and his experience of the Apollo 1 disaster, the “story so far” of the space race, and the personal stories of the three astronauts and their wives. In the main arc, the crew get their official responsibilities: Borman the commander, Lovell the navigator, and Anders the systems engineer. Thousands of people and many departments must coordinate to keep the mission on track. The crew spends hundreds of hours training in a messy-looking simulator. The Saturn V is transported at a staggering one mile per hour from the Vehicle Assembly Building to the launchpad.

On October 11th, Apollo 7 launches. Despite constant grumbling from the mission’s commander (broadcast all across America), it completes all of its objectives. As Apollo 8 draws closer, many both in NASA and in the media are openly discussing the danger of the mission, with The Washington Post painting the endeavor as an irresponsible publicity stunt. In November, Chris Kraft convinces Admiral John McCain to allow NASA to use the Navy’s aircraft carriers to recover the command module after splashdown in the Pacific. In Washington, Apollo 8 still has not been officially approved. Many NASA managers still have reservations, including George Mueller, Associated Administrator for Manned Space Flight. Kraft is furious at Mueller’s obstructionism, but he cannot deny the risks of the mission.

On November 11th, NASA chief Thomas Paine phones President Lyndon Johnson and tells him NASA has officially approved Apollo 8. The next day, Paine shares the news with the media. Three days later, the director of NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston receives a letter from a man named Stewart Atkinson urging a delay of Apollo 8. “This is by no means a sure venture,” Atkinson writes, “and the risk of ruining the Christmas Season for millions of Americans is enormous.” Atkinson is not wrong. During all of this, the Soviet Union’s unmanned Zond 6 is flawlessly executing a free-return trajectory around the Moon.

In November, Frank Borman’s wife, Susan, asks Christ Kraft what the odds are the mission will succeed. Kraft gives her an honest answer: “How’s fifty-fifty?” For Susan, that’s just fine.

On December 15th, NASA begins its official launch countdown.

On December 20th, Soviet cosmonaut Gherman Titov indicates that few in the Soviet Union actually believe the Saturn V will launch the next day.

On December 21st, it does.

The Saturn V slowly but surely lifts itself into the air. It gains speed, soaring into the sky above a crowd of spectators and visible to millions at home, including the crew’s families. At an altitude of 215,000 feet, the first stage separates. At 300,000 feet, the escape tower is discarded. The Saturn V inserts into Low Earth Orbit. The second stage separates. The third stage ignites, bringing the craft to a speed of 17,425 miles per hour. Apollo 8 is now orbiting the Earth.

From here, everything the crew does is a first and has mission control and their families on the edges of their seats. The third stage engine successfully delivers the ship into a trajectory toward the moon. Kurson takes this moment to devote a chapter to describing the American troubles of 1968 in more detail, from the pro-segregation presidential campaign of George Wallace to the Vietnam War to the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy.

Back in space, Frank Borman conducts a successful test of the lunar module separation maneuver, which would be critical for Apollo 11 in the future. Mission Control clenches their teeth as Apollo 8 passes through the radiation-filled Van Allen belts, terrified that the crew will have some terrible effect on the crew. Anders, a nuclear engineer, reassures Houston that radiation levels remain safe.

Eleven hours after launch, Christ Kraft is pacing in Mission Control. The Service Propulsion System engine was just fired to implement a minor correction, and although the trajectory was properly corrected, the engine did not fire as predicted. After hours of pouring over data from the firing, Mission Control concludes this was most likely due to a bubble trapped in the engine’s propellant line, which at this point would be gone. The next time the SPS engine is fired, it will be to conduct the critical injection maneuver into Lunar orbit; so they had better be right.

Meanwhile, Frank Borman gets sick and his crewmates have the historical honor of becoming the first humans to experience cleaning up vomit in zero-gravity.

As Apollo 8 nears the moon, the astronauts make their first television broadcast. Unfortunately, the Moon is not yet visible; but it is a historic broadcast nonetheless. After another minor correction, Apollo 8 disappears behind the Moon, losing communications. Kurson takes this moment to give a brief history of the Moon and humanity’s study of it. On Christmas Eve, Apollo 8 successfully inserts into Lunar orbit. As the spacecraft emerges from the far side of the Moon, Anders takes the opportunity to capture the historic Earthrise photograph. On Christmas, Apollo 8 makes its second broadcast, sending back video and descriptions of the Lunar surface. As the sun emerges from behind the Moon, Bill Anders reads aloud the first words from the book of Genesis. He closes with, “good night, good luck, a Merry Christmas, and God bless all of you – all of you on the good Earth.”

After a few more orbits, Apollo 8 once again passes behind the Moon, losing contact with Earth. The SPS engine fires again, with the intention of sending the crew back toward Earth. To many on Earth – at NASA and in the homes of the astronauts – this is where it could all go wrong. Burn too short and the crew would be trapped in Lunar orbit forever. Burn too long and they would be flung off into space, never to return. At 12:19 a.m., Houston regains contact. Jim Lovell gets to deliver the good news: “Please be informed – there is a Santa Claus.”

On the way back to Earth, Lovell makes a typo on the navigation keyboard and accidentally resets the Apollo 8 guidance system – suddenly, the flight computer now thinks the spacecraft is back on the launchpad. For a few terrifying moments, no one knows which way is up. However, using the Moon, the stars, and his knowledge of astronomy, Lovell is able to reorient the craft and get the control system back on the right settings. A bit later, Apollo 8 makes its third and final broadcast back to the people of Earth, giving them a tour of the capsule and describing life in space.

The day after Christmas, Apollo 8 burns through the Earth’s atmosphere and splashes down in the Pacific. The crew become celebrities and national heroes. The world is alight with praise for the mission. Even the Soviet Union says that Apollo 8’s success “goes beyond the limits of a national achievement and marks a stage in the development of the universal culture of Earthmen.”

Amidst thousands of telegrams from politicians and celebrities, one from an anonymous stranger travels across a broken America to reach the White House of a tired President, addressed to Frank Borman, Bill Anders, and Jim Lovell.

“THANKS. YOU SAVED 1968.”

Chris Kraft and other managers in mission control during Apollo 8. Original image from NASA, downloaded from Hack the Moon.

The above summary may seem too lengthy or detailed, but the truth is it is impossible to capture everything that makes Apollo 8 a story of engineering without including the details above. Rocket Men is a treasure trove of systems engineering lessons.

No system is perfect, and the Apollo 8 mission was no exception. From accidental life-vest inflations to space vomit to engine bubbles to simple typos, there was plenty that went wrong throughout the mission. What was important was that the system was able to continue to operate as intended despite these problems. And this touches on an important lesson from the book: the people are just as much a part of the system as the machines. Apollo 8 never could have succeeded without Borman, Lovell, and Anders. When the life vest accidentally inflated, the crew figured out a way to safely deflate it without poisoning themselves with carbon dioxide. When Borman got sick, Lovell and Anders were able to clean up after him. When Lovell accidentally reset the flight controller, he was able to improvise and reorient the ship. And it was not only the crew who were crucial, but their wives who spent hours speaking with media in support of the mission, the NASA employees who convinced the government to give their approval, Christ Kraft getting the Navy to lend NASA their ships – all of this and more went into the success of Apollo 8 just as much as the rockets and computers.

One of the most important scenes in the book is Kraft and Borman’s initial meeting to sketch out a mission agenda. The entire exchange is a rich lesson in systems engineering. To begin, the room is filled with different stakeholders, all with different needs. The mission planners want as much data as possible. The trajectory analysts want a safe path to and from the Moon. Kraft wants to put on a good show for America. Borman wants as little risk possible in order to ensure his crew survives. These needs often come into conflict. The mission planners want as many Lunar orbits as possible to gain experience for a future Moon landing. Borman refuses, as every extra orbit was an extra chance for things to go wrong. The team eventually lands on a compromise of ten orbits.

This scene also shows the importance of thinking practically when designing a system. When Borman first proposes ten orbits, the trajectory analysists refuse, saying the timing would require the craft to splash down in the dark; no one would be able to see if the parachutes malfunctioned. Borman shoots back, “What the hell does that matter? If the chute works, great. If it doesn’t, we’re all dead and it won’t make a difference if anyone can see us.” The analysts can’t argue. Ten orbits it is.

However, the most insightful moment in this meeting is an argument between Borman and Kraft. Borman hates the TV cameras, calling them a distraction. He wants them gone. Kraft responds that this is a historical mission that the American people need to see. Borman doesn’t care. “We’re here to do a job.” Kraft answers with a Hollywood-worthy line: “That’s part of the job.”

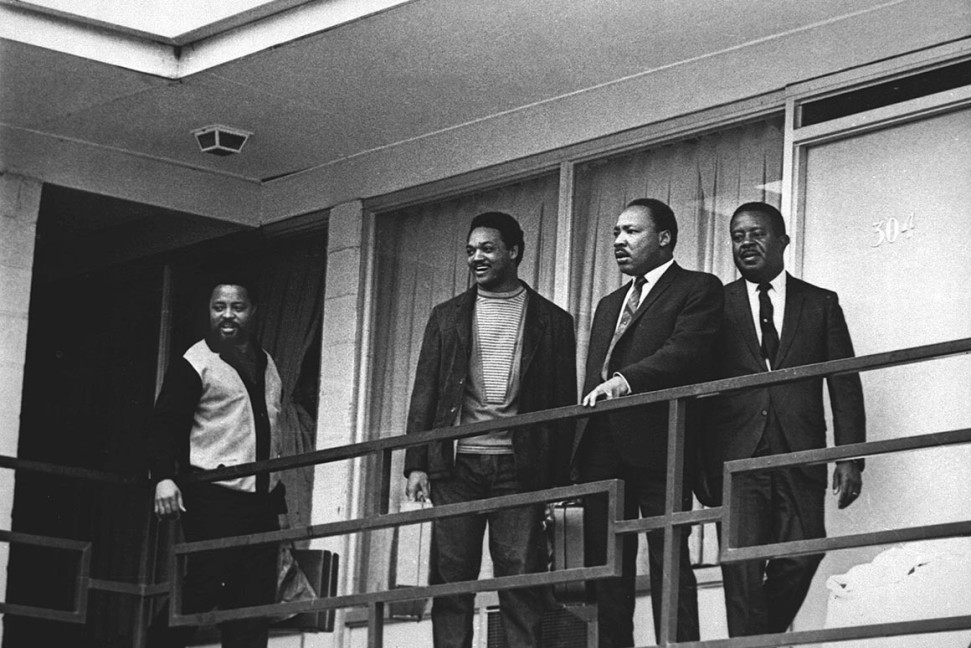

Martin Luther King Jr. on April 3, 1968. He was assassinated one day later. Original image from Charles Kelly/AP Photo, downloaded from Politico.

Rocket Men is brilliantly-written and tirelessly-researched and presents a true story in a genuinely exciting way. Kurson is amazing at taking real historical events and weaving them into a narrative both educational and engaging. He not only tells a great story about a heroic crew, but he also understands the importance of examining how those on Earth experienced Apollo 8. From the astronauts’ wives to their children to those at Mission Control, Kurson doesn’t let the reader forget that this is about more than just Borman, Lovell, and Anders. The funny moments draw laughter, the inspiring moments invoke smiles, and the tense moments are written in a way that makes the reader feel just how frightening and anxiety-inducing the mission was at times. By the end, the book is truly difficult to put down.

That said, Rocket Men has its issues. It is non-fiction, but it is written with an undeniable bias. Although Kurson makes some modest attempts to seem like an objective journalist, for the most part he can’t resist the urge to write an epic tale of heroes on a grand quest to conquer an insurmountable goal. In fairness, this is part of what makes the book so engaging; but romanticizing Apollo 8 necessarily leaves out some important aspects of the story. For one, Kurson allows a couple pages to discuss some of the common reservations about the mission, such as Mr. Atkinson’s letter. However, an entire book could be written about all the reasons why Apollo 8 was, quite frankly, a terrible idea. The mission was rushed and extremely risky, filled with all sorts of dangerous challenges that NASA had never conquered before. And, as Atkinson aptly pointed out, it would all take place at Christmas – a failure would have rendered the holiday a day of tragedy for all Americans, then and now. It’s easy to look back and say that Apollo 8 is a tale of courage and daring, but the truth is, NASA placed the crew at extraordinary risk for what was, in many ways, simply a multi-billion-dollar public relations stunt for America. That is not to say instilling national pride and hope did not have its merits in the Cold War era, but doing so at such extreme risk was controversial for good reason.

It has also been implied already that the book leans a bit too hard into American exceptionalism. This is, again, a consequence of romanticizing the story. Astronauts in the 60s were military men and Borman’s primary motivation in commanding the mission was to serve his country. It probably would not have been possible to garner the necessary support for Apollo 8 without playing into a narrative about the greatness of the US and the evil of the Soviet Union – and, to his credit, Kurson does do his best to avoid falling into the cliché “America good Communism bad” narrative often found in Cold War histories. But more could (and should) have been done to address the legitimate problems with America as a nation at the time. Kurson tends to discuss the societal problems of 1968 as if they are symptoms of some sort of disease that the victim US just happened to contract. But these were real problems with deep roots in America’s history. Yes, America is the country that first sent men to the moon, but it is also the country that prolonged the Vietnam War and killed Martin Luther King Jr. and built up a governmental and economic system engineered to keep power in the hands of white men – white men like Borman, Lovell, and Anders. That is a side of the story that Kurson does not give enough attention to.

For all the engineering efforts that went into Apollo 8 – for all the math and programming and complex astrodynamics – the mission was, at its heart, a show. It was a show to instill hope and pride in the American people. It was a show to prove to the Soviet Union that America was a formidable rival. It was a show to announce to the whole world, America is a nation that does great things. And these theatrical goals were essential when designing the system. That’s why Kraft refused to scrap the TV cameras. That’s why Earthrise exists. That’s why Anders read from the Bible on Christmas Day while filming the Lunar sunrise. That’s why Lovell put a cute Christmas spin on things when he radioed back to confirm successful insertion into a return trajectory. And that is the ultimate takeaway of Rocket Men: that all this stagecraft was as crucial to the Apollo 8 system as the SPS engine or the Saturn V’s first stage. Because the true mission was not to orbit the Moon or to break the altitude record or to obtain the Earthrise photo. It was not to test how humans react to passing through the Van Allen belts or to find out what it takes to clean up vomit in zero-gravity. All of these were how’s, not what’s. The mission of Apollo 8 was simple: to save 1968.